by Kelsey Wynn | Editor in Chief

SCRANTON – A teacher at Bnos Yisroel Jewish girls’ high school in Scranton is using Aquinas articles from the 1930s and 40s to teach her second classroom adaption of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s History Unfolded project.

History Unfolded is a project conducted by the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., which asks students, teachers and historians throughout the nation to conduct their own research into archived newspaper and journal databases to uncover how much – or how little – Americans knew about the Holocaust as it was unfolding, and their response.

According to the museum’s website, participants in the project search about the Nazi threat in the early half of the 1900s. As of Nov. 11, 4,563 participants have submitted over 41,100 stories from their local newspapers, which have been located in all 50 states.

“Through their work, these “citizen historians” have learned about Holocaust history, used primary sources in historical research, and challenged assumptions about American knowledge of and responses to the Holocaust,” the website says.

Kristen Andrews, a history teacher at the 15-student Bnos Yisroel, said the school already has a historia class that teaches Jewish history. As a U.S. history teacher, however, she said she was looking for an outside-the-box way to teach the Holocaust from the American perspective. History Unfolded caught her eye.

“This was not part of their teaching resources at the time, but they were doing this nationwide project and they were looking for people to be what they call ‘citizen historians’… It’s kind of a complicated question – What did the United States know?” Andrews said.

Two years ago, Andrews began researching locally because she wanted to help out with the project overall.

“I thought to myself, ‘Oh, I can help out, I can look through the Scranton Republican‘… Then it dawned on me that I could use that in my classroom, but instead of looking at what the average American or adult in Scranton knew or read at the time, I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could find out what students knew?” Andrews said.

To begin her first classroom adaptation of the national project, Andrews turned to archived versions of The Aquinas, which the University of Scranton keeps online in a digitized database.

Andrews pointed out that the term holocaust came after the events unfolded, so searching articles for The Holocaust as a proper noun was not the most feasible approach.

“You can’t search for the word holocaust, so what do you search for?” Andrews said.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) has denoted 41 specific Holocaust-era events to categorize and refine article searches, including events such as the staging of nationwide book burnings by German students and Nazis on May 10, 1933, and Hitler’s announcement of the Nuremberg Race Laws, defining Jews as a race and stripping their citizenship rights, on Sept. 15, 1935. These events, Andrews said, were crucial when exploring the University’s archives to design her project.

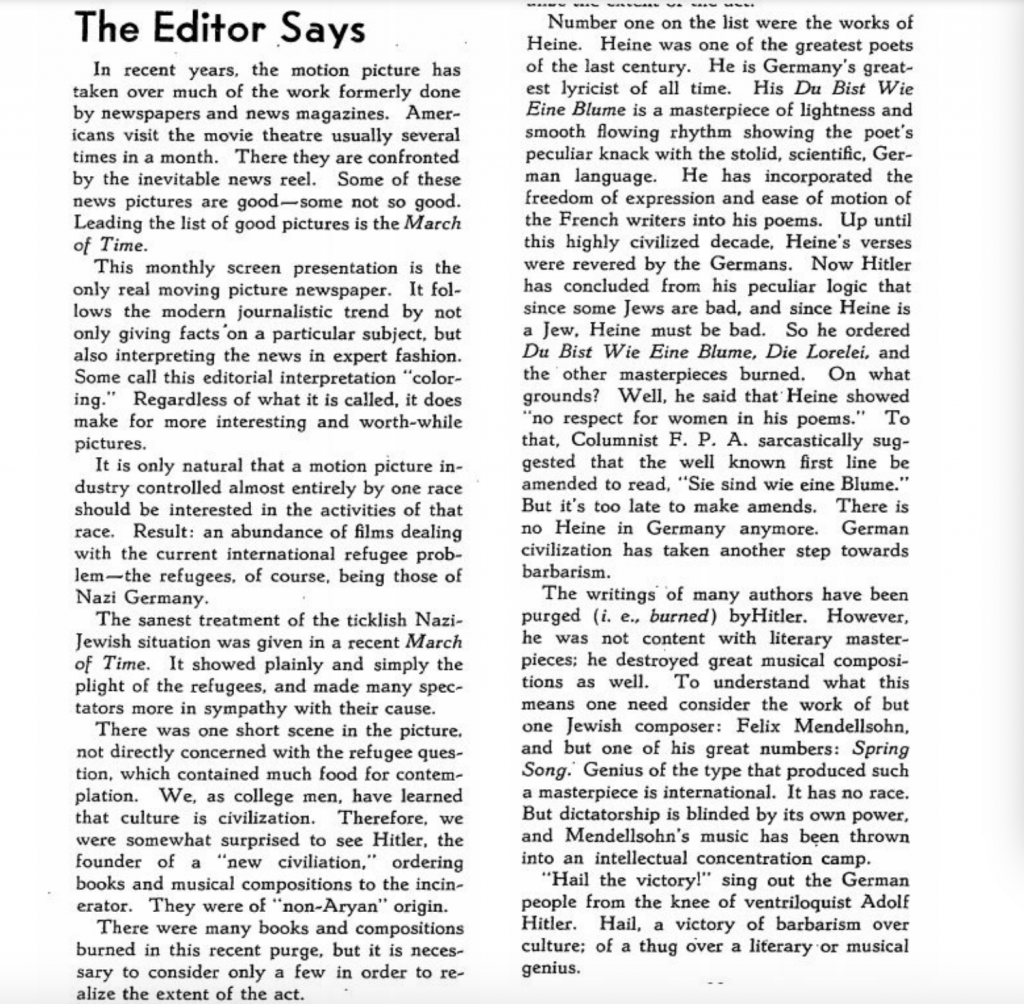

Her research led to the incorporation of four Aquinas articles in Andrews’ 20-question project for 11th and 12th graders, including clips from The Aquinas Vol. II, No. 15 and No. 22; The Aquinas Vol. VIII, No. 13, and The Aquinas Vol. X, No. 12, when the University was still St. Thomas College.

Andrews said that she got so excited about finding the articles, and the third article – a letter by The Aquinas editor in 1939 – inspired what she said was one of the best outcomes of the project – discussing artistic contributions.

“[The editor was] talking about something that would be really interesting to college students at the time, which was the Nazi book burnings and the bans that they had placed on any kind of art or literature or music that was written by a Jew. They declared that they were all dangerous and needed to be destroyed,” Andrews said.

Some of those “dangerous” artworks referenced in the article include Heinrich Heine’s poem, “Du Bist Wie Eine,” which translates to, “You are so like a flower” and acknowledges the beauty of another person, and Felix Mendelssohn’s “Spring Song.” The editor questioned in his article, upon what grounds were works he called “genius” and “a masterpiece of lightness and smooth flowing rhythm” being burned? Andrews and her students wish to uncover the same answers.

“It’s a beautiful poem… And we were kind of like, well why would they say that’s a bad thing? How is that offensive to anyone?” Andrews said.

The history teacher’s project has asked students to consider questions such as, “What assumptions are made about Jews in this article,” “Are the assumptions treated as possibilities or facts,” “What is the false danger mentioned in the end of the article,” and “So what is the real danger then?”

This, Andrews said, turned out to be a highly complex question for Americans living through what would come to be known at The Holocaust. Currently conducting her project for the second time two years after her first go-round, Andrews said the questions of what Americans knew and why they didn’t stop some of those events from unfolding are still just as complex, but she has learned a lesson in how to teach these types of questions.

“One of the most valuable things I’ve learned from [my students] and teaching The Holocaust is don’t try to give simple answers to complex questions. It’s easy in history when you’re teaching young children to just say, ‘Yeah, Columbus discovered America,’ but we all know that it’s a much more complicated story. So this was a means to answer a complex question without just giving a simple answer like, ‘Americans didn’t really know that much,'” Andrews said.

According to Andrews, her students weren’t looking for a simple answer either. There was so much discussion on the project’s first day in the classroom, Andrews said they barely got through the first article.

“Immediately [the students] were like, ‘Thank you so much, this was so interesting.’ This is an engaging thing. This is a conversation that we’re having,” Andrews said.

Andrews said the availability of archived newspapers, like The Aquinas, through online databases is something revolutionary and crucial to future research, which she said has also helped her show her students that history isn’t dead.

“There are so many questions that still aren’t answered… There are still new discoveries that we can make. Years ago I’m sure The Aquinas archives weren’t digitized, well now they are. So this is how that turns in to new historical research, even though this is something that happened 80 years ago,” Andrews said.